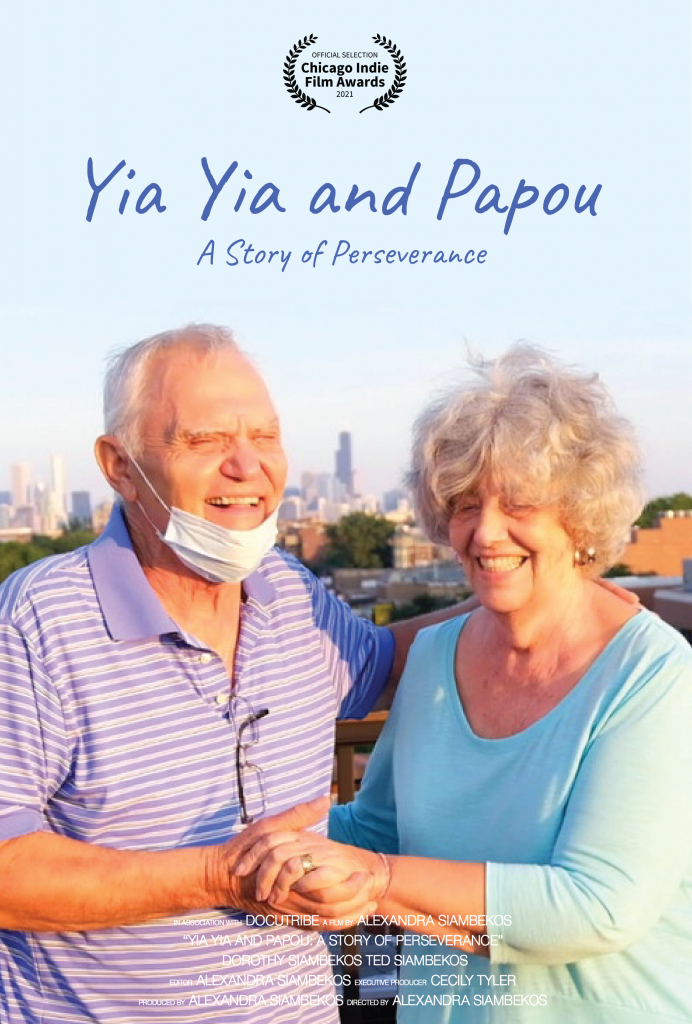

By Alexandra Siambekos

Twenty-Twenty was full of chaos and uncertainty. For most of the year, I was at home with my family. I decided to look inward and explore the legacy living right next door: my grandparents.

Dorothy (my Yia Yia) and Theodore (my Papou) Siambekos are hardworking and resilient—and certainly stubborn. It is what drives their unconditional love, which has endured a lifetime. They will go any lengths to care for and protect their family.

While making this film, I listened to them retell moments of happiness and hardship from their lenses as a first-generation Macedonian American and Greek immigrant. I thought I was familiar with their story, but what was new was their emotional vulnerability—which they rarely show.

As a filmmaker, I documented and preserved their legacy. As a young adult, I learned from their wisdom. And as their granddaughter, I honored them for all the sacrifices they have made and continue to make for family.

TRANSCPIRT

March 11, 2020

[Ominous, instrumental music plays]

Tedros Ghebreyesus: W.H.O. has been assessing this outbreak around the clock. We have, therefore, made the assessment that COVID-19 can be characterized as a pandemic.

Lester Holt: The coronavirus outbreak declared a global pandemic. President Trump addressing the nation from the Oval Office tonight.

President Donald Trump: Today, the World Health Organization officially announced that this is a global pandemic.

Linsey Davis: We begin tonight with a troubling barrage of coronavirus headlines, and many fear that this is only the beginning.

[Music stops]

Alexandra: Hi, Yia Yia.

Yia Yia: Hi, Alexandra.

Alexandra: Thank you.

Yia Yia: You’re welcome.

[Alexandra laughs]

Yia Yia: Bye, bye.

Alexandra: Bye.

Sophia: Are they too close?

Alexandra: What? No.

Yia Yia: Yeah, that is.

[Alexandra and Sophia laugh]

Sophia: Let me pull this chair—

Yia Yia: Your shirt’s all dirty.

Papou: How’s it dirty?

Alexandra: You want to put your arm around her, Papou?

Yia Yia: He might choke me.

Alexandra: That’s good.

Yia Yia: This is all fake now, I don’t know why you’re doing fake. You’re supposed to look at the camera.

[Alexandra laughs]

Papou: No, she’s not ready yet.

Yia Yia: She’s taping.

Papou: No, she’s not. Are you?

Upbringing

[Man speaks Greek on iPad]

Papou: This is the department of music. Yeah.

[Greek music briefly plays]

Papou: I grew up in a village in Manaris. My oldest sister, her name was Yanoula, second oldest was Vasio, and I was third, and my brother was fourth, and my brother Takis, and Nikki was the last one. There was five of us.

[Goat bells]

Papou: We’re out there, there was no, no electricity, no running water, no nothing. Just plain village life, that’s all it was.

[Waves on the shore, distant boat horn]

Papou: My father brought me to boat.

Alexandra: And what did he say to you before you left?

Papou: What did he say? He hugged me and kissed me and said, “Goodbye, good luck, and don’t forget home. Take care of us.” So, I was on a boat for 14 days, and then I arrived in New York: June 6th, 1951.

Yia Yia: My parents had a huge garden. My father always canned everything in jars: peppers, tomatoes, pears. I mean, everything was fresh.

Alexandra: Where did you grow up?

Yia Yia: In Chicago.

[Dog barking]

Yia Yia: My neighborhood was like all old homes, and it was mainly a Czechoslovak-Bohemian neighborhood—and there were other ethnic groups. It was nice. You’d walk six blocks down to almost Kedzie. There were stores. They had Goldblatt’s, Kaplan’s, Lourie Brothers. You always walked, you’re walking, walking, because we didn’t have a car.

Yia Yia: My parents were both from Yugoslavia in Macedonia. My father spoke a little English, my mother was broken English. My oldest brother was Bobby, the second oldest was Willie, and I was the third, and my youngest brother was Johnny.

Papou: My uncle, my father’s brother had this store, we had an ice cream parlor—and then we lived upstairs. After my uncle passed, in 1953 he passed away, and then I was left alone. Then I started working. [Laughs] I was making ice cream sundaes, I shined shoes, I washed windows, I worked in restaurants. You name it I did it back then.

Yia Yia: Our house was at the end.

[Clinking glasses, people chatting]

Yia Yia: My parents always entertained, we always had company. They would come and they’d sing, and tell jokes, and sing. They were dancing and everything. Good memories, you know, really, I mean. It was good. [Sniffles] I shouldn’t.

Alexandra: No, you’re okay, do you need to take a moment?

Yia Yia: Yeah.

Alexandra: It’s okay.

Yia Yia: You’re not taping.

Alexandra: [Laughs] You’re okay, it’s okay.

Yia Yia: I’m sorry.

Alexandra: You’re very—you think of your childhood very fondly, and that’s really great.

Papou: My education was limited. I came here, I didn’t speak English. I went to the College of Hard Knocks. On the street, that’s where I learned everything. Then I went to Sears, and I got the truck job. And then during that time, I got drafted, I went in the service—in 1960. I was in Fort Riley, Kansas, for two years. After that, I came back. I went back to my old job.

Love

[Lawn mower]

Yia Yia: It won’t start. I can’t start it, I can’t. He always starts it. [Laughs]

Alexandra: Should we go get him?

Alexandra [to Papou]: Yia Yia needs your help.

Papou: For what?

Alexandra: To start the mower. She can’t start it, in the back.

Papou: Okay, what are you doing?

[Lawn mower starts]

Alexandra: Woah, one try!

Papou: I met Yia Yia when I was on 26th street and Pulaski.

Yia Yia: There was a hot dog stand on 28th and Pulaski, and John had it. He was friends with John, so we just knew him because a lot of the Greeks were with the Macedonians. Then he kept coming around and coming around.

Papou: And we started going out and going out. We always went to the dances; you know, the Macedonian dances. Well, we went there, and I used to go there, then we danced, and then— finally—you know, we started going out. Her mom says, “When are you gonna marry my daughter?” because we used to go out all the time.

Yia Yia: The only thing my father said: “Greeks gamble a lot.” And he said, “You gamble?” and he goes, “No.” So, he said okay. That’s the only thing my father said. And that’s it.

Alexandra: When was the first time you said I love you to Yia Yia?

Papou: [Laughs] I can’t remember, honest. It’s 53 years ago.

Yia Yia: Now that’s a crazy question.

Alexandra: Wasn’t there a moment of realization that you thought, you know, he’s, he’s the one?

Yia Yia: Love is blind! [Laughs]

Alexandra: [Laughs] Really.

Papou: So, then we got married.

[“Maria Me Ta Kitrina” music plays]

Purpose

Sophia: I mean, think about it. At one point you had three of us in college, at different places, you had Steve still in school, here. You got laid off, at one point, when I was a senior in high school—I remember that. Then you were sick a couple years later, and then we were all in school like a snap. I mean, and I guess as a child, I knew it wasn’t easy. But now, as I think about it as a parent, I’m like, “How in the hell did you do it?”

Yia Yia: Christ was born, 1967.

Papou: And in 68, your mom was born.

Yia Yia: Maria was born four years later, 1972, and Steve was born six years later, 1978.

Papou: And I just kept working, and Mom stayed home, Yia Yia stayed home. She took care of the kids.

Yia Yia: I always said—my mother didn’t speak much English, and they didn’t have activities like when I went to school what they have now—but I said, “If I ever get married, I’m gonna do everything I can for my children.” I was on the board for the baseball league, and I was on the PTO. And I used to make all their costumes and enter them in the Pet Parade. That was my life. I gave everything to my children. They came first. You know, that means a lot to me. You know, so that’s it. You know.

Yia Yia: When my children were little, every day I had a meal for them, and I always made a dessert.

Alexandra: You cooked a homemade meal every day?

Yia Yia: Every day I had a whole meal.

[“Makedonsko Devojče” plays]

[Garage door opening]

Yia Yia: Ted worked late hours.

Papou: I started at eight o’clock and I’d finish, at eight, seven, nine, ten. To start with, you know, I was a helper. I worked with an electrician, and I’d pull wires, I did this, I did this, and then through the years—after a while—I used to go to do the job myself. But I never took big jobs, only small jobs. And don’t forget I was, I was doing this stuff all my life. I worked average, I think, 60 hours, 55—well as much, as many as I could. But, at the same time, we didn’t have nobody to help us anyway, you know, like my family was all in Europe.

Alexandra: What motivated you to work so hard?

Papou: Well, no, well, here’s the thing. Motivate because I had a family. Every day I went to work, I was happy to go to work, and I always make sure that I took care of my family. That’s all it was.

Yia Yia: We didn’t live luxuriously to spend money foolishly. It was all the money, was for the children, for school.

Papou: Family goal was education, education, education—at any cost. We did not start talking about going to school—going to college—when they got 18 years old. We started talking about it when they were five years old, they knew they gonna go to college. There’s two ways to make a living: you gonna use your mind, or you gonna use your back. Every time one of my kids graduated college, I was very proud. When I got the receipt, they give me—all my kids they gave me— “Dad, here’s your receipt”—when that they gave me the, the diploma. Every time I got one of them, I was very happy.”

Papou: Being a parent, that’s the proudest you can be.

Yia Yia: That’s what you live for. You say, “Thank God they’re healthy, and they’re good.”

Papou: Everybody was healthy. So, that’s the main thing. We had, we had no problems. For our family we’ll do anything, but Yia Yia will do ten times more than me. So, that’s how she, that’s how she is.

Alexandra: My Yia Yia and Papou have taught me to live with purpose. The main thing that was driving their life was family, and then education. And as long as they had that in their sight, they could achieve anything—they could achieve that goal. And I think that’s why their story serves as a constant reminder that I also need to work hard to achieve what I want to achieve, and, and work hard for my family, and for those I love.

Strength

[Chimes]

Papou: The hardest moment is when I was, when I was sick.

Yia Yia: I had two children in college. Steve was, I believe, nine years old or ten, and Maria was a sophomore in high school. Ted wasn’t feeling well, and I told him to go to the doctor. He went to the doctor. He had cancer. So, the doctor came, and he said to me, “Your husband has cancer. I don’t think he’ll live till September, if you’re lucky.” And I said, “Isn’t there anything you can do?” “No, there’s nothing.” They told me he was gonna to die, and I never told any of my kids. Never, never, never. You know, I didn’t want to worry anybody.

Papou: Yia Yia, she couldn’t take no for an answer, so she started checking and checking, until finally when we went somewhere else, and that doctor said, “You’re gonna go through hell, you’re gonna suffer,” or whatever it is, but he said, “You’re gonna be fine.”

Yia Yia: Every time I went to the doctor: “I’m gonna die, I’m gonna die.” That’s all I heard, like I didn’t have enough of problems. I had four kids, and he’s telling me how he’s gonna die. So, I got up and I yelled, and I said, “You’re not gonna die, you’re gonna live to make me miserable. So, shut up.” And here he is, 30-something years, and making me miserable, and he’s still alive. [Laughs]

[Morning birds]

Yia Yia: He had to move around. He had a recliner here, and I took it out.

Papou: The doctor said, “Walk every day, as much as you can.” So, that’s what I’m doing. So, I kind of started a program here, and I try to follow it.

Yia Yia: You know, you’re married so long, you know if something’s wrong or that. And you just do it because you don’t want anything to happen to him.

Papou: That was the hardest moment of my life. I was 50 years old when that happened.

Yia Yia: Everything worked out. He got better, and better, and better; he started gaining weight then.

Papou: We passed that hurdle and things went on.

Legacy

Papou: The only job you start at the top is when you start digging the holes. The rest of the job, you start at the bottom, and you work your way up. If you want to get something done, you gotta work for it. That’s what I did, all my life.

Yia Yia: So, I mean I couldn’t do what I did before—when I was younger. You know, I’m 80 now. But I try. I keep going.

Alexandra: To be remembered as someone who did everything for their family, who worked hard every day for their family to make sure their kids went to school. And I mean, I just, not that I want to lead the same lives they did—because that’s not possible. But I hope to even come close to the amount of love that they have for their family, for the amount of strength that they have, resilience that they have, that’s, that’s what I strive to be.

Yia Yia: Here, try this. [inaudible]

Alexandra: Does it look like I’m struggling?

Yia Yia: [inaudible]

Alexandra: I’m working.

Yia Yia: Try this, just, I want you to try it.

Alexandra: Okay.

Alexandra: And family is part of that legacy. I’m part of that legacy. And going forward, I’m going to have all of the lessons they’ve taught me, the wisdom they taught me, to help guide me through my life ahead.

Alexandra: Being home, from March until now, is probably the longest time that I’ve spent with my grandparents. In my whole life. They live right next door now. And it was hard being at school and being at home, but you know—at the same time—it was one of the most rewarding experiences because I’ve been at home with my grandparents for almost a full year. And I’m really sad that when I go, I won’t have that—physically.

Y: Relax and that. I hope everything goes your way.

Papou: Bye, love. I just want you to know: Take care of yourself, and use your head, and don’t sit on your brains.

Alexandra: I’m just really grateful to have the grandparents that I have. And, um. Man, I’m really sad to see them go. I mean—not like they’re going anywhere, but I’m going any—gosh. [Laughs] But I know that they always be there for me, and they’ll always be with me.

[“In the Mood” plays]

Sophia: Come on, Ted.

[Alexandra laughs]

Yia Yia: Come on! She wants to tape it for that thing, damn it!

[Alexandra laughs]

Papou: Oohh, I can’t get up. Oohh.

[“In the Mood” ends]

Alexandra: Ayyy.

Sophia: Dad’s crying!

Credits

Yia Yia: See my posture, Alexandra?

Sophia: Yia Yia’s, got a little on her face.

Yia Yia: What?

Alexandra: So, I need to, uh—

Yia Yia: I have something on my face?

[Papou dances to Greek music]

Yia Yia: This way nobody knows we had ice cream.

Alexandra: Do we want to keep this a secret?

Yia Yia: Do you want to throw it in the garbage there?

Alexandra: I’m tilting this.

Papou: No, no, no, no, I said the, the high or low.

Yia Yia: I’ll do what I do all the time.

Alexandra: Whatever you want to do. Ya, do what you do all the time.

Yia Yia: Fall asleep, Ted.

[Yia Yia, Papou, and Alexandra laugh]

Papou: [Laughs] Nah, I’m not falling.

[“Everybody Needs Somebody” plays]

Yia Yia: I need you, you, you. I need you, you, you.

[Laughter]

Yia Yia: You know, I didn’t say shit. You noticed that. Or did I? I probably didn’t realize it.

Sophia: Your interview will be beep-beep, beep, beep, beep, beep, beep—

Yia Yia: [Laughs] Beep, beep, beep, beep. The whole thing.

Yia Yia: Oh my god, it was—Oh, you did such a great job.

Papou: Good job, Alexandra. For your first project, this is great.

Yia Yia: Oh my god, great? Great-est. Great, great, great.

Papou: That’s fine. Nice, nice job. Very good. Thank you.

Yia Yia: No, you did a great job.

Alexandra Siambekos is a junior at the S.I. Newhouse School of Public Communications, pursuing a degree in Television, Radio, and Film with a minor in Anthropology. Through her film, Yia Yia and Papou: A Story of Perseverance, she sought to highlight vulnerable communities impacted by COVID-19 and capture an intimate portrait of her grandparents.